The last time the NEO Endurance Series visited the Autódromo José Carlos Pace on February 21, 2016, the result was the most controversial race the series has ever seen. We revisit that infamous event in this oral history of the 6 Hours of Interlagos from season two.

It was just past the midway point of the race, but you would have never guessed if you were in race control. Protests were still rolling in at the rate often expected from the first prototype trip through traffic, and 29 incidents had already been investigated.

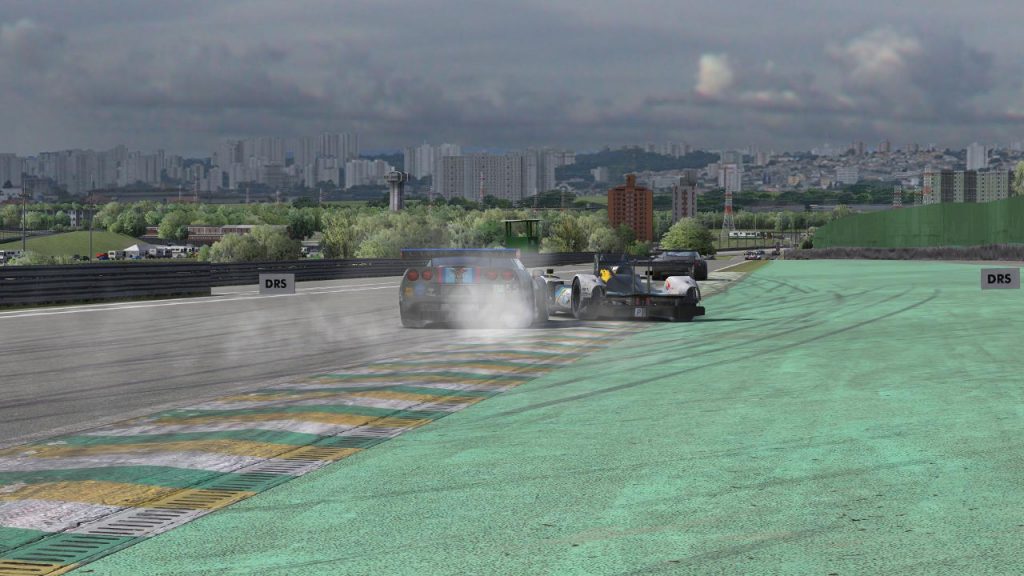

Suddenly, a new issue popped onto the officials’ radar. The ACME Racing HPD rear-ended the wounded GoT Racing Ford GT, which ricocheted their already-damaged car into the right front of the IRDK Endurance Corvette.

It was a crash that included cars in all three classes, and even the RaceSpot commentators seemed to recognize it as a desperate time that called for desperate measures.

That track was almost blocked there, observed Wil Vincent, head of commentary for RaceSpot TV. That would have been the second time today I would have thought we might well have had ourselves a Code 60, Cam.

Well, almost, added Cam Walsh, who also worked the broadcast for RaceSpot. But you know, I think it’s one of those things where nobody even thinks about using them. I’m not even sure if they tried to throw it out that people would…

Walsh trailed off as another close call occurred on track.

Ooh, heavens!

Officials in race control, led by series co-founder and director Niel Hekkens, had the same thought as Vincent, but for a different reason.

“We were absolutely done with the amount of incidents,” said Hekkens. “Especially because they were absolutely avoidable in our eyes. We felt the need to gather all team managers and talk to them.”

And thus, for the first and only time in series history, the entire field of cars — or at least those that were left after the numerous early instances of car contact — slowed to a crawl as officials deployed a full-course yellow flag.

But that crash, and the caution period that followed, was in many ways the end of a story — the culmination of a season’s worth of frustration on behalf of everyone involved in the series.

This is that story. This is the tale of the day the racing stopped.

It’s a bit of an understatement to say that the NEO Endurance Series had enjoyed a meteoric rise up the ranks on iRacing. There was high demand for an organized league that would sanction and implement the long-awaited team endurance racing feature. In fact, the grid for the first season — which was set by first-come, first-serve registrations — was filled in just 15 minutes.

For the second season beginning in the fall of 2015, series officials implemented the now-standard pre-qualifying process intended to identify the fastest and cleanest teams among the many contenders hoping to join the grid.

However, after three races in the seven-round season, the racing hadn’t been as clean as expected. Following the 6 Hours of Watkins Glen, officials released a Driving Standards Improvement document outlining several procedural changes geared toward making multiclass interactions safer and the protest system more transparent.

Beginning at January’s 8 Hours of Spa, drivers briefings would clearly define track limits, Friday free practice sessions would be open to individual drivers with the hope of having more cars on track together, and stewards would aim to hear from all parties involved in a protest before making a ruling.

The rulebook was also updated to include a “penalty matrix” designed to more severely punish repeat offenders and provide separate penalties for three common infractions: unjustifiable risk, barging, and avoidable contact.

While it all seemed a bit bureaucratic for a racing game — er, simulation — the goal was actually to make understanding incidents more straightforward for both competitors and officials.

“Teams and drivers would know why they got such a severe penalty, and for us, it’s easier to pick the penalty that is defined for a certain violation,” explained Hekkens.

However, even that didn’t solve the problem in the eyes of the officials.

“Teams were still driving a bit over their heads and we were still wondering what we can do, because tougher penalties clearly were not the answer,” said Alvin Nieves, a past and current NEO steward who was in race control during the controversial Interlagos race.

Given the ongoing issues with driving standards, and with that track next on the schedule, officials tried to get ahead of any potential problems.

The drivers briefing email that went out the week before the race noted that this is a small track, where it can be very tough to pass. That turned out to be an understatement.

“We did expect some issues due to the compact nature of the circuit,” said Hekkens. “Especially at the second sector.”

While an incident in that winding, slow-speed infield section appeared to be the catalyst for the full-course yellow, the initial incidents happened elsewhere. The first penalty of the race went to an unlikely offender — the frontrunners from Friction Racing — for an unsafe rejoin after a spin at turn 1.

“Interlagos turn 1 is quite a tricky braking zone, and I just spun on entry,” said Marcus Hamilton, now with Thrustmaster Mivano Racing. “I’m pretty sure I stayed on track, though, so perhaps it was a little harsh to be penalized as technically I was never rejoining the track, nor was there contact with anyone else.”

It wasn’t the only issue at turn 1 that day. The heavy braking zone and downhill corner proved to be particularly difficult for GT1 teams to manage.

“I believe it was Stefan [Muijselaar]’s first race in the Corvette and it was not easy to drive,” said Anders Dahl, then with Vergil Racing. “You had to run the brake bias quite low to avoid locking into T1, especially with the tires at the time. Stefan simply pushed the pedal a bit too much and around it went.”

For Vergil, there was no recovery from Muijselaar’s spin on lap 104.

“Unfortunately there was a quite solid concrete wall on the inside and that was it,” added Dahl.

Together with the corner that followed, the Senna S at the beginning of a lap around Interlagos was a danger zone for GT drivers, even without traffic.

“With the lower downforce on those GT1 cars, you had to be extra gentle under the brakes,” recalled Jason Gerard from the Excelsior Racing Team, whose Aston Martin finished fourth in the GT1 class in the race.

“The Senna S was where races went to die. Either misjudging the entry or taking too much of the kerbing on driver’s right at the bottom of the hill, and there were many who had issues with both.”

The tight, tricky circuit was like a short fuse that was all too easy to ignite. It was no wonder, then, that after enough strikes of a match, the entire powder keg eventually went off.

For officials, the Interlagos race represented the worst of the already bad driving they’d seen, especially from prototypes, during the season.

“It was so chaotic, like nobody was taking care of themselves,” said Nieves. “I get that Interlagos is sort of a short track for multiclass, but with it being wide, overtaking should not be an issue. We were just seeing penalty after penalty and no light at the end of the tunnel.”

In the eyes of some prototype drivers, though, this race was less about poor driving standards and more about officiating standards — or double standards, as they saw it. In several situations that season, prototypes had been penalized for incidents even when it seemed like a GT driver was at least partially at fault.

That may have been due in part to a bit of institutional knowledge ingrained in the minds of both drivers and officials, which meant GT cars were typically given the benefit of the doubt when contact occurred with a prototype.

“New and old drivers alike have had the old adage ‘it is the responsibility of the faster class to make the pass safely’ drilled into them,” said Team Chimera’s Simon Trendell, “to such an extent that personal responsibility or self preservation on the part of the slower classes isn’t being taken into as much consideration as it should be.”

Whether it was because of such a long-held mindset, the increased amount of multiclass interactions, or the very nature of the Interlagos circuit, this race brought those frustrations to a boil.

Turn 3 was another frequent trouble spot, as prototypes making an outside pass could find themselves in a collision if the GT car to their left tracked out on corner exit.

GT drivers contend that it’s a turn where they need to use every bit of the road and can’t easily watch their mirrors to check for faster cars approaching behind them.

However, prototype drivers argue that multiclass racing requires effort on both ends, and that corner is a great example of it.

“You watch the real-life races and see how the GT drivers also leave room, not always tracking all the way out and leaving, for example, the outside of Pouhon open when the faster car is close enough,” said Sahil Mustac, driver of the ACME HPD at the time of its accident.

“It’s give and take. GT cars don’t always have to stay on the racing line and track out perfectly, with the HPDs having to be the only careful car.”

With these competing visions of how traffic management should work in turn 3, it’s no surprise that it was the scene of the crime for the second penalty of the race. And no one — officials or drivers in any of the three classes — were surprised at who the perpetrator was.

The newly formed all-Spanish squad of Odox Motorsport made their NEO debut in season two. Their talent was undeniable; they made the competitive HPD field in pre-qualifying and they even qualified for the inaugural iRacing Blancpain GT World Championship Series.

However, the driving at the start of their first NEO season had been a bit rough around the edges, to put it nicely. The team received four penalties at Sebring and two more at Watkins Glen. All but one were for avoidable contact.

It was a troubling trend that officials felt compelled to address.

“There was one team who was very bad in multiclass racing and other teams were demanding us to ban this team,” said Hekkens about Odox.

“Nobody wrecks people on purpose, so I decided to start a conversation with them. By doing that, I found out this was their first multiclass experience. Ever. I gave them tips and linked them various videos or other resources.”

While some of their competitors had run out of patience after their rash of early-season incidents, Hekkens was willing to give Odox a second chance.

By the Interlagos round, the team was a work in progress. Their only penalty in the preceding 8 Hours of Spa was for barging — not a more severe avoidable contact infraction — and concerns about their driving within the league had largely quieted down.

However, just 25 minutes into the Interlagos race, Odox ran afoul of the rules yet again. Juan Jose Sanchez encountered slower traffic in turn 3 and simply ran beyond the kerbing to complete the pass.

After serving a stop-and-hold penalty for exceeding track limits, Sanchez fell to the back the prototype field but was still running. Less than 15 minutes after his first incident, he had another — this time for barging the #65 Hammer Down Racing Corvette.

For officials, those violations were clear-cut based on the regulations. But for teams, not all rules seemed to be created — or enforced — equally.

The ongoing race against the rulebook then took an interesting turn at the hands of a potentially unlikely source: a GT entry.

Team Chimera fielded both a prototype and a GT1 Aston Martin in season two. In a previous race, their #24 prototype team was penalized for making a pass even when no contact occurred. From that point on, their teammates in the GT car took it upon themselves to protest other prototypes for similar moves.

“Prior to Interlagos, our HPD was penalized for ‘passing two cars in a single corner’ during the Spa round, which then became a specific definition of ‘unjustifiable risk’ within the rulebook,” said Trendell.

“We objected, because in the GT1 we were regularly passed at the same time as other cars through corners without any issues whatsoever. So from that point onwards, whenever it did happen, we protested it.”

Call it a principled stance, a chip on their shoulders, or a ploy to aid their teammates. In any case, when Trendell found himself on the receiving end of divebombs from both the Vortex Racing and Fenix Motorsports HPDs, his team filed protests — one of which resulted in a penalty, and the other in a warning.

“We would rather have avoided protesting Vortex and Fenix because from memory, neither incident was particularly disruptive in the grand scheme of things, but the situation with the #24 at Spa made us feel it was the only option to illustrate our grievance. Otherwise it would be one rule for us, and another rule for others,” added Trendell.

“Thankfully this served to highlight how poorly that rule interfered with the normal, fluid nature of the traffic, and also how it was unrealistic to properly enforce.”

For Vortex and driver Gabor Mecs, who now runs with Thrustmaster Mivano Racing’s #4 P1 entry, the penalty came as a surprise.

“As I remember, I was not happy about the penalty,” he said. “I always try to give my best with traffic management. I would never like to cause any trouble, of course, and this is a hard genre as we know.”

While Mecs and Vortex escaped further penalties the rest of the day, the same couldn’t be said for Fenix, whose race was about to get even more hectic.

Indeed, Fenix’s divebomb on Chimera wasn’t their last or most egregious-looking incident of the race. On lap 54 during his second stint behind the wheel, Richard Hollyday hit the Torrent Motorsports Ford GT in turn 3, bulldozing the Ford off the track and into the wall.

Observers including the broadcast commentators chalked it up to another out-of-control prototype.

This incident, from the angles I’ve seen it so far, that is just completely unacceptable to run a racer off the track like that, said Vincent.

I don’t think he even lifted until after he hit the car, Walsh added. I have a feeling Torrent Motorsports, the entire team isn’t going to be happy campers there.

They most definitely were not.

“The first part of the race before the crash happened, we were satisfied with the pace that we had, so a top five was our target, but unfortunately it got ruined by the Fenix HPD,” said Kevin Siggy, who was driving the Torrent Ford at the time of the accident.

“Our reaction was pretty much the same as always: raging for a brief minute then a cool-off as time goes on. We ended up protesting the team for careless driving and ruining our race so it was frustrating to say the least.”

It was a move that defied explanation, at least until after the race, when Hollyday posted his side of the story on the forums.

If you want to upgrade my DSL so that every car on track doesn’t vanish all at once, be my guest, said Hollyday at the time.

Despite the answer and an apology that accompanied it, Torrent wasn’t exactly appeased. Siggy’s teammate Jordan Weekes had a less-than-forgiving response to Hollyday.

I’m sorry but that is no excuse at all and to act like an ass toward me isn’t going to help you out at all.

That sort of snippy exchange in some ways defined the overall atmosphere of the NEO Endurance Series’ second season.

The addition of more top teams and drivers meant closer, fiercer battles on track. And those high-level drivers and their sometimes-inflated egos didn’t stop competing once the races were finished.

“The atmosphere was certainly more contentious during that season,” said Gerard. “A lot more drivers calling out other drivers and teams calling out race control in public. A lot more vitriol being spewed on the iRacing forum boards. I would say that things were more immature back in those days.”

Concerns over the quality of multiclass racing in iRacing’s top endurance league was one divisive issue, and the Driving Standards Improvement manifesto was the response by series officials.

But drivers still didn’t see eye-to-eye with officials or even one another about every issue, including the balance of performance between the two GT1 cars — the Corvette C6.R and the Aston Martin DBR9.

“It was the first time we ran multiple cars in one class,” said Hekkens. “This was a new experience for the officials, the teams, and the drivers.”

After winning the first four races of the season and taking nine of the twelve podium positions, Aston Martin teams received an extra 5 kilograms of ballast beginning at the Interlagos race. That decision only further stirred the pot, as they felt a weight penalty wouldn’t equalize the difference between the two cars.

“I believe the issue wasn’t with single-lap pace but more how the Corvette was slightly harder on its tires, which meant it was slightly slower over a full stint,” noted Trendell. “Generally, the Corvette had better straight-line speed at the expensive of being more difficult to drive and set up, whereas the Aston was slower at the top end but would be easier to drive.”

Managing those two very different cars was an almost impossible task for officials given their limited options of adding ballast and reducing fuel tank capacity.

“Some people think that we have the keys to the kingdom and can just open the file and start editing,” said Nieves. “We wish, but that is not the case. We could also ask some teams to provide data, but who puts billy goats to look after a lettuce crop?”

In an already frustrating season, the balance of performance debate simply added another millstone around the officials’ necks. By Interlagos, they — and the series as a whole — were on the verge of drowning.

After numerous additional warnings and penalties were handed out during the second hour of the race for every newly detailed violation in the series regulations, it appeared the chaos had finally calmed down.

A full sixteen minutes passed between protests received, so for a brief moment, it gave Hekkens a chance to reflect on the series and its future — if there was even going to be one.

Behind the scenes, the tense atmosphere and constant scrutiny of officiating decisions had Hekkens debating whether to keep NEO going for a third season and beyond. The turmoil took away much of the fun factor and had him on the verge of pulling the plug.

“I think we were very close, as we didn’t enjoy organizing that much, in that moment,” he said.

Nieves speculated that the still-young NEO was nearly a victim of its rapid growth and the work required to keep it running.

“I think it was a combination of seeing so many things that have to be looked after for things to run smoothly. It was only our second season, and it’s amazing that no matter how much things are discussed during the off-season, there is always something that we could not see coming and then we are pulling our hair at that,” he said.

“But one thing we have learned as a series is that mistakes will happen. Own them and move on.”

As the on-track incidents resumed, officials began debating what action they could take. They just hoped their next decision wouldn’t be one of those mistakes.

In the season two rulebook, along with the more controversial regulations surrounding driving standards and penalties, laid a far more innocuous provision — rule 5.12:

Race control may declare a Full-Course Yellow (FCY) period if they decide it’s necessary. Race control shall do this via the @RACECONTROL channel and send a message to live timing.

While safety cars and virtual safety cars have become relatively common in global motorsports, they remain much rarer in sim racing, where there are no worries about stranded cars, course workers, or debris on track after an accident.

“Originally, the full-course yellow procedure was designed for very major incidents or any other major problems,” explained Hekkens.

“The sim racing community is very sensitive when it comes to safety cars,” he said, so “going into the second season, we replaced the safety car procedure with the full-course yellow/Code 60. It is quicker and a bit more ‘fair’, because the gaps between the cars are roughly maintained.”

Ultimately, the rule saw its first and only implementation in a NEO race not because of a catastrophic accident, but as something of a last resort for officials at the ends of their ropes.

“As race control we were not mad, but very disappointed in the teams and the drivers on the track,” said Hekkens. “As we got more disappointed and annoyed over time, we started discussing what to do.”

That discussion involved all of the officials, and it wasn’t a decision they took lightly.

“We knew it may cause a backlash on us, but we felt it was the right decision at the moment,” said Nieves.

Hekkens doesn’t blame one particular moment, such as the three-car crash in turn 9, for putting officials over the edge and throwing the caution. Instead, he credits “a lot of identical incidents” that they felt needed to be addressed.

However, that crash was probably the most visible example — shown live on the broadcast — of the sort of incident officials wanted to stop.

For at least one of the teams involved in it, though, the full-course yellow was too little, too late to save their race.

Even at a 2.677-mile circuit, lap 128 at Interlagos for the GoT Racing team was one of their longest and most eventful of the season, with a pair of incidents that derailed their race.

Until 3.5 hours in, everything went according to plan, wrote Marco Derix after the race. We were fuel saving like crazy and would’ve made it with five pit stops without any problems. Then the s#!t hit the fan.

A HPD spun right in front of us in turn 1, [and] our driver managed to stop without hitting it, but the GT1 and HPD behind us weren’t paying attention and slammed right in to our back.

That spinning HPD belonged to KRT Motorsport’s Bryan Carey, who would find himself caught up in more controversy in the same section of the track a few laps later.

Derix was just a car length behind Carey when the spin occurred, and despite checking up in time, the Falcon GP GT1 and the Team 7A Racing HPD that entered turn 1 bumper to bumper couldn’t hit the brakes soon enough to avoid a domino-like collision between all four cars.

GoT suffered the worst of the damage, forcing driver Robbert de Rooij to circulate the infield section at 90 kilometers per hour en route to the pit lane. But his trip there suffered one more unexpected delay, as Derix explained.

While limping back to the pits, another HPD thought it was a good idea to slam on the gas while driving just a meter behind us. He spun us around, and we got hit once again, this time in the side of the car.

Derix didn’t name names, but anyone watching the race knew exactly which HPD it was.

ACME Racing started in fourteenth and was running twelfth at the time of the incident, having driven a clean race and largely a clean season. In fact, the penalty they received at Interlagos was their first in the opening five rounds.

Mustac was caught off guard by the slow speed of the GoT Ford, which meant a normally routine lane change on corner exit resulted in contact.

“I saw other HPDs in front of me having to go around the Ford, and I saw some of the damage, but by the time I had sights on it, we were in the turn and the car seemed to be tracking fairly normally,” recalled Mustac recently.

“Looking at the replay, the car was full-on crabbing down the straights. Definitely something I did not anticipate. I should’ve done a better job, but it all happened so quickly.”

Mustac shouldered most of the blame for the incident on the broadcast, on the forums, and in the eyes of race control. Looking back, he says he could have approached the situation differently, but overall it was just a bad position to be in.

“I was in the wrong place, wrong time, yet could have done a better job of avoiding it if I’d been maybe a bit more aware of the situation,” he said.

However, he remains disappointed that the slow speed of the GT car was not considered by officials, given that a regulation stated damaged cars could only be driven back to the pits if they were “able to maintain a speed of at least 50% the racing pace”.

“I felt let down by the stewards more than anything,” he added.

Regardless of how it happened, the crash set into motion the full-course yellow, and business was about to pick up for everyone involved.

True to this race’s form, even the transition to the full-course yellow wasn’t entirely smooth. Over the voice chat, Hekkens gave a countdown until drivers on track needed to apply their pit speed limiter or otherwise slow to 72 kilometers per hour.

Although he followed that procedure as written in the regulations, not everyone got the message. Some teams expected a text-based countdown, while others missed the voice command entirely.

One such driver was Bryan Carey in KRT’s #18 prototype. As the countdown was ongoing, he was approaching the Blue Flag Racing Corvette in turn 2. The GT1 car applied its speed limiter mid-corner, but Carey continued driving as usual, spinning the Corvette and adding another incident for officials to investigate.

“Clearly I didn’t get the call,” remembered Carey.

His teammates watched it all play out as they waited for him to react.

“When they started [the countdown], I assumed Bryan was hearing it too, but he must have had it on a different channel or something,” said KRT team manager Andy Fuller. “I had assumed he could hear it, but I was wrong and we were in traffic when it happened, so the wreck happened.”

“When it was called, I was spotting and had to tell Bryan a few times to slow down and engage the limiter,” said Dean Moll, now a driver for the iRacing Today Motorsports P2 team. “It was in the regulations but we didn’t expect it, so that was not ideal how we hit another car and didn’t react quickly enough.”

Carey wasn’t the only one who missed the message. Danilo Piazza in the #17 Team 7A Racing HPD continued driving at race speed down the frontstretch and was later given a two-minute stop-and-hold penalty for passing under yellow.

Even the prototype leader didn’t initially get the signal, and as cars slowed around him, Team Chimera’s Ben Tusting assumed they were running out of fuel.

“Ben had the wrong device set as his iRacing voice output and didn’t get the audio message,” said Chimera’s Jamie Wilson.

“Of course, we didn’t realize that at the time, so there was some brief confusion initially. Once we realized he hadn’t received the message, we relayed instructions as quickly as we could and, from memory, we ran slower than the designated speed for a while to try and compensate for the delay.”

Their sustained pace for several seconds after the full-course yellow came out didn’t go unnoticed by their competitors. Chimera was investigated, but officials did not penalize them since they gave back the time gained initially.

“Other teams were right to protest it, but the compensation that we had applied ourselves was ultimately just beyond the amount required,” said Wilson.

For the officials, it was important to make sure no teams cheated or outright ignored the full-course yellow procedures, but given the rarity of the situation, they also offered some leniency.

“We did take into account that some cars slowed down earlier or later than others,” noted Hekkens. “This is very normal, as drivers always push the limits. This happens in real life as well. I believe we decided not to do anything about teams winning a couple of seconds during the full-course yellow.”

That was also in part because Hekkens had a captive audience awaiting his arrival.

After the prototype team managers had gathered at Hekkens’ request, their meeting wasn’t exactly cordial.

“I don’t remember the exact words, but one thing you never want to hear is an angry Niel,” said Nieves.

Hekkens did recall a few of the choice words he had for teams.

“I think we asked them ‘what the hell is going on?’,” he said. “We told them that it’s their responsibility to not only look after your own car, but also for the cars around them.”

Managers who were at the meeting had a similar recollection of the discussion.

“I attended the meeting,” said Fuller. “It was stressed there should be cleaner racing between the classes. I think there were a bunch of bad interactions between the P2s and the other classes.”

For many prototype team managers who had been focused on their own race, this was the first they had heard about the widespread nature of the problems.

“Clearly the organization were unhappy with the amount of incidents going on,” said Hamilton, “but I was largely unaware of them so it was all a bit surprising to me.”

Officials also told prototype teams not to expect much sympathy given the quality of the racing so far.

“As an organization, we can only do so much,” said Nieves. “It’s up to the ones driving the racecars to do their part, use their brain, leave their egos at the door, and use common sense.”

While prototype team managers were getting an earful from race control, teams in all classes were debating the potential impacts of the caution on their strategy.

Because the yellow flew near the beginning or middle of a stint for most teams, a pit stop wouldn’t have been very useful for them. But since a trip down the pit lane was essentially free, many of them worried about how it could help their rivals.

“We were saving fuel the entire race in order to do one less stop than our competition. In that regard, it did help us a little bit as it cut down on actual racing time,” said Sven Deml from the class-winning SimRC.de Ford GT team.

“Due to our strategy, we did not consider pitting at the time of the full-course yellow, but we were worried our competition might use that opportunity as it seemed like a good time to come in for them.”

Friction Racing was one of only two prototypes — the other being the damaged Odox HPD — and seven cars overall to stop under the full-course yellow, as their early penalty threw them off-sequence and made it an opportune time to hit pit road.

“Fred [Evers] was driving at the time, so I made the call for him to pit,” said Hamilton. “We had to do virtually a whole lap before Fred could get back to the pit lane, though, so there was still a chance the race could go green before we reached the pits.”

Ironically, the caution to address the bevy of prototype penalties allowed them to claw back some of the time they lost serving their own penalty earlier in the race.

“In the end, it was definitely beneficial for us, and allowed us to catch up by about 20 seconds,” added Hamilton, “sadly not completely cancelling out our penalty, though.”

After completing a full slow-speed lap around Interlagos — one that some teams used to debate strategy, others spent getting a tongue-lashing from officials, while a few more pondered how they’d missed the command that issued the yellow flag in the first place — it was time to go racing once again.

To conclude the 4-minute, 18-second full-course yellow, Hekkens — fresh off his rendezvous with prototype team managers — recited another countdown to bring the race back under green-flag conditions.

Often lost among the incidents was the fact that this was a race, and at times a damn good one, especially at the front of the field.

Chimera’s prototype entry fancied themselves as underdogs all season compared to the likes of Coanda SimSport and Team Radicals. After winning earlier in the season on another tight track at Circuit of the Americas, they found more success at Interlagos, but it didn’t come without a fight.

Early on, they waged a side-by-side battle with Coanda for the lead, with driver Jack Keithley using a GT2 car as a pick on lap 8 to take the top spot. And after the full-course yellow ended, they led by less than four seconds over Radicals. By the end of the race, they had extended that lead to the winning margin of 14 seconds.

“Interlagos wasn’t a victory that fell to us just by good fortune. It was won by tackling those two giants of endurance head on and coming out on top,” said Wilson.

“For us, a relative minnow in comparison, those races are the greatest achievements in our history.”

In the two GT classes, familiar names finished first due to both a strong pace and (mostly) clean driving. Thrustmaster Mivano Racing’s #31 Aston Martin won the GT1 class with Tommaso Carlà and Fabio Gonzalez behind the wheel. It was the team’s third win of the season.

In the GT2 class, even the race-winning SimRC.de team couldn’t completely escape incidents. Despite their best-laid plans — “we always made notes about the drivers in other teams and talked extensively about on-track behavior,” recalls Deml — they were caught up in someone else’s problem.

“There was a big mess in the Senna S as we were approaching the corner two-wide with a GT1 car,” he said. “While avoiding the stationary cars on track, we made contact with the GT1 car and ended up spinning ourselves. We were lucky not to hit the wall so we could get going again without any serious damage.”

Within the GT2 field that was decimated by incidents in traffic, SimRC had both the speed and survival needed to succeed.

The full-course yellow didn’t single-handedly fix NEO’s problems, either in the eyes of officials or drivers. In the remaining two-and-a-half hours of the race, stewards investigated 15 more incidents with penalties handed out for five of them.

All but two penalties issued in the race were to prototype teams, and even some GT drivers felt they got away with mistakes as prototypes became the scapegoats.

Gerard recalled an incident on the second lap of his stint when he raced side-by-side with a lap-down GT1 into turn 1 as faster traffic approached.

“We literally had five cars from all three classes converging on the same space. I got a little spooked by the HPD and ended up driving up the track a little under the brakes and into the lapped GT1,” he said.

“If memory serves, they gave the penalty to the HPD. We suspected that it may have had to do with the ‘conversation’ that the stewards had with the HPD teams.”

Even non-penalized incidents were a continuing source of frustration for prototype teams. Contact in the final laps of the race in turn 3 between the KRT prototype and the IRDK Corvette warranted a post-race investigation.

While no further action was taken, KRT was still disappointed in the officials’ response.

“Race control called it a racing incident but stressed I wasn’t racing for position and the GT car was. That annoyed me a little since I felt like I did the right thing in the overtake and was wrecked by the GT,” said Fuller.

“After that race, I was a little sour on the entire series since nobody really ever asked the GT driver why he tracked out and hit me. It was just another wreck blamed on the P2.”

Fuller held back from venting on the forums, but not everyone showed the same restraint. In the hours and days following the checkered flag, the often-cordial rehashing and discussion of the race’s events became heated, even by season two’s standards.

Some comments were critical of the officiating, while others defended it.

If you guys are trying to drive Niel insane, I would imagine it’s working, speculated Troy Schuster.

In other cases, drivers went after each other. Taking center stage was the argument between Derix and Mustac, which was at times passive aggressive, but mostly just aggressive.

Love your twisted version of events, wrote Mustac. Gives credence to why when I came up on the 99 with you in the car after FCY, you blocked me for 3 turns. I’m sure you’re very proud of the sportsmanship you showed there.

He also echoed a familiar refrain among prototype teams from season two.

HPDs are expected to read traffic and make safe moves. Why are GTs not expected to do the same? Why are they full-attack at every turn?

Nearly three years later, while Mustac describes the incident and its aftermath more diplomatically, he said he wouldn’t take back any of his post-race comments.

“What I said was exactly what I meant. I was in a terrible spot with other GT2s around me, was trying to race the HPDs in front who we had started catching later in the runs, and had a genuine chance to make the pass.”

If Mustac, his competitors, and the race officials could agree about anything after Interlagos, it’s probably that few of them left the track feeling happy. With two races left in the season — at Monza and the Nurburgring — they all had to find a way to pick up the pieces and move on.

Whether or not the airing of grievances during and after Interlagos had anything to do with it, the state of the series, from the driving standards to the overall atmosphere, did improve in the rest of the season.

While there were no further rule changes — “I don’t think we did anything else after Interlagos”, said Hekkens — teams generally found comfort racing within the regulations, whether they liked them or not.

“Looking at the protest sheet, the penultimate round was much better in terms of the number of incidents,” Hekkens recalled. “I don’t remember any major issues in the season finale, but I guess that is a good thing.”

Since season two, officials have developed a more keen eye when reviewing incidents so prototypes aren’t automatically at fault for any contact with a GT car.

“I think we got better over the seasons. You gain more experience in recognizing the key moments,” said Hekkens.

“Two of the most important questions we ask ourselves are, where is the faster car at the moment when both start braking, and where is the faster car at the moment when the slower car starts to turn in? We also compare the braking and turn-in points of both cars from previous laps.”

Prototype teams were also relieved when the controversial terms of the unjustifiable risk rule that frowned upon “multiple faster cars overtaking a slower-class car in the same corner” were discarded at the season’s end.

Even while fighting that rule during season two, Team Chimera credited race control’s “eagerness to learn from any negatives” as part of their constructive conversation with officials.

But it has to be done in a positive way, noted Wilson in a forum post after Interlagos. Niel has expressed recently that this hasn’t been happening as much as it should be. In the heat of the moment, tension will of course be high — we were furious immediately after Spa, for example — but we can all address this problem in a civil way without resorting to just simple arguing.

While racers may never agree on everything, for the sake of the series, it was best if they could all just get along.

In any good relationship — or at least a six-month living arrangement as in NEO — open and honest communication is a key. That turned out to be one answer to NEO’s problems, and it happened in all directions.

Between race control and team managers. Between teams and officials. From one driver to another. And even from the series to Odox.

In fact, by the end of the season, Odox had become masters instead of missiles in multiclass situations.

By [the] Nürburgring, #14 was actually the third-most trusted HPD for me to be seen in the mirror after GoT and Coanda, shared Fenix GT2 driver Roope Turkilla after the season finale. Looking forward to see Odox in the field next season.

Odox have, in fact, returned to NEO every season since then and have become upstanding veterans on the grid — a far cry from their initial inexperience. In season five, they field both a P1 prototype and a GT Porsche.

For all teams, despite several early incidents in the most recent race at COTA, officials have noticed that the quality of the multiclass racing in NEO has generally been on the increase since season two.

“It goes up and down,” said Hekkens. “It is expected to have more incidents at the start of the season. Overall, I think the standards have improved over the years.”

Derix, who was among those criticizing NEO race control during season two and demanding more severe consequences for incidents, later became a series official and was a witness to their improved decision-making process.

“I think that the stewards’ decisions have become more clear or similar for the same kinds of incidents,” he said. “Every incident is looked at by at least two people, and most of the time, three. That way, we hope the decisions stay as fair as possible.”

For officials, the proof is in the protests — or lack thereof — especially late last season.

“My personal highlight, as a steward, is season four’s 24 Hours of Le Mans,” said Hekkens. “There we had only 18 reported incidents in the entire race and we also had a period of seven hours where no incident was reported.”

Interlagos is not Le Mans, of course, and as NEO prepares to return to the Brazilian circuit — this time with the even-quicker P1 cars — drivers and officials are hesitant to predict a completely clean race next weekend.

Believing that old habits die hard, some series participants in both the prototype and GT classes expect the worst this time around, with each citing a similar cause for concern about one another.

“There are big egos in categories who don’t want to lift even for a millisecond to help the faster class a bit,” said P1 driver Mecs. “And of course no one wants to lose much time behind slower cars, because the faster your car, the more time you lose.”

“I expect nothing but careless driving, since this is how all the prototype classes work,” countered Siggy. “It has happened at COTA and it will happen here too, because people have an ego and that’s how the iRacing prototype community is like.”

Other drivers are more optimistic, even offering tips for how to manage traffic in the race.

“Perhaps the fast left-hander at turn 3 is the easiest to misjudge,” said Hamilton, “as it’s flat out for all cars normally, but judging whether to pass on the outside or wait for the inside line to clear isn’t a straightforward decision. The rest of the track offers a lot of opportunities to pass so you don’t really get held up too much.”

While Deml won’t be in the race this year to defend his GT class victory, expect his SimRC.de teammates to take a similar approach as last time.

“The race at Interlagos was pretty far into the season already so we knew what teams and drivers to look out for. We made sure to be very assertive in denying them the opportunity to pass in dangerous spots and gave them extra space once we allowed them through as to not take any risks,” he said.

“All the usual things, being predictable and aware of your surroundings, are obviously necessary as well.”

Officials also hope that drivers will remember the endurance aspect of the race, exercising patience instead of making the sort of risky moves that caused such chaos three years ago.

“It will be a very challenging round for the teams and drivers,” said Hekkens. “It’s a very short track and very crowded. Pure pace is less relevant. Staying out of trouble will be key here.”

Nieves noted that while this year’s race will include up to 13 more cars — 55 are on the entry list compared to 42 in season two — the GTE cars also have higher mid-corner speeds than their GT1 and GT2 predecessors, which could help make for smoother multiclass interactions through Interlagos’s tightest turns.

“Considering all three classes have significant downforce, it should ease things a bit in terms of being at the limits on some parts of the track,” he said. “I would say whoever can manage traffic better from Ferradura to Junção during six hours will come on top of their respective classes.”

Even if everyone is on their best behavior, having so many cars on such a small circuit still promises to provide plenty of close-quarters drama. It’s certain to be another action-filled race for drivers, officials, and broadcasters alike.

Almost three years after it happened, the season-two race at Interlagos remains one of the lowest points in NEO history, as some of iRacing’s top prototype teams were told their driving wasn’t up to par, and building race-long and season-long frustrations festered after the race.

Perhaps it was also an inflection point for the series. NEO’s increasing prestige and competition level meant heightened scrutiny from everyone, toward everyone. Something had to give. And it wasn’t the series itself.

Instead, it was an opportunity to gain experience, maturity, and accountability — the same lessons officials drove home in their meeting with prototype team managers.

“One of the takeaways from that season is that it’s not entirely the responsibility of the organization to improve driving standards,” said Hekkens. “It’s up to the drivers to look after themselves and each other. Teams and drivers need to take responsibility for their own actions.”

While incidents still happen, the overall atmosphere in NEO has significantly improved since season two.

Relationships between drivers even on rival teams are friendly as evidenced by the positive conversations on Discord — because posting on the iRacing forums is so two years ago.

Tensions over officiating and balance of performance are at an all-time low.

NEO is in no danger of closing its doors, having sanctioned 16 races (and counting) over four different seasons since the last trip to Interlagos.

And even for drivers who fear history repeating itself in the return to Sao Paulo, they can take comfort in knowing the full-course yellow provision is no longer a part of the NEO sporting regulations.

With any luck, we’ve seen the racing stop on track for the first — and last — time in this series.

Related posts

Latest news

Race Replay: 6H SPA

BMW Team BS+TURNER win 12H BARCELONA

Race Replay: 12H Barcelona

- iRacing Staff Member Profile: Senior Creative and Graphics Manager Larry Fulcher

- FIA SIMAGIC F4 eSports Regional Tour Week 6 report: Rubilar extends lead, Ladic and Dunne take over in respective regions

- THIS WEEK: Skip Barber Formula iRacing Series Hot Lap Qualifier at VIR Grand

- This Week in iRacing: July 23-29, 2024

- ExoCross Storms Onto PC and Console Platforms